|

The Troy

Smelter Site

in the Dripping Springs Mountains

of Central Arizona

|

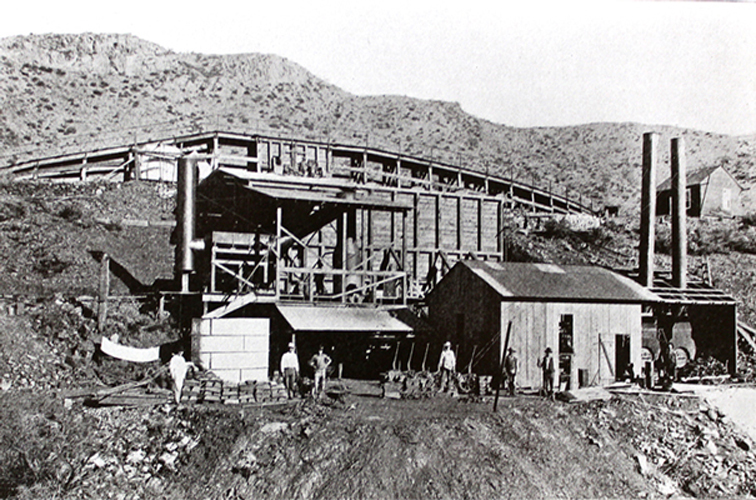

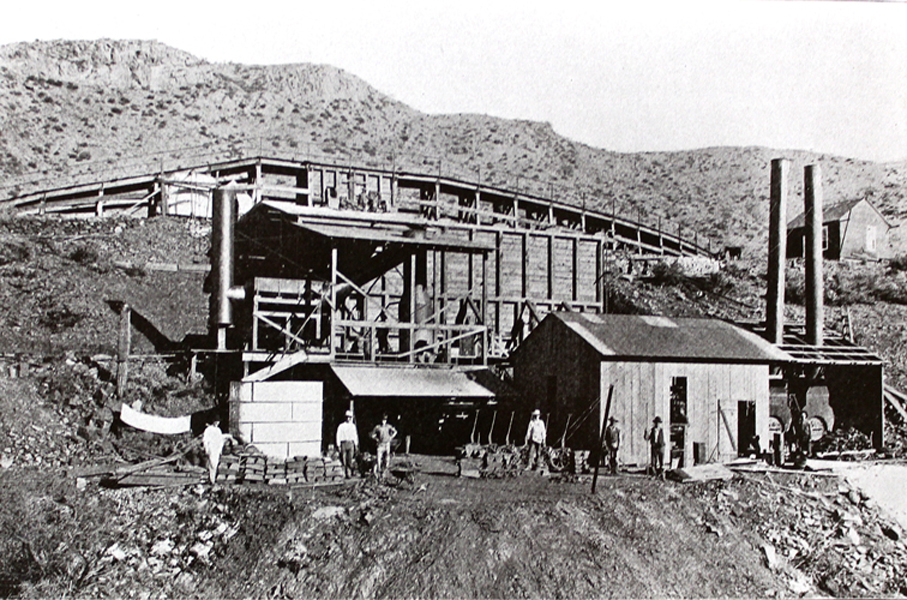

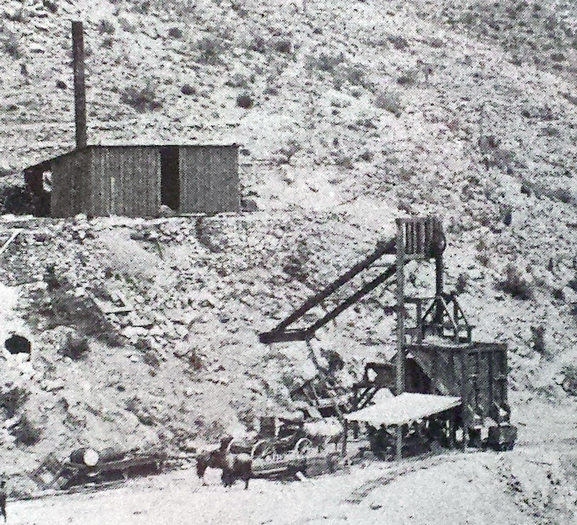

In 2007, while on a hike to several mines in the Dripping Springs Mountains, I paused for a quick look around the Troy Smelter site. Several years later, I came across this photo which seemed to show the smelter in a complete and operating condition. I thought that I should return to the site and photograph its current state from the same perspective as that of the vintage photo. I finally made it back to the area in 2016.

|

|

There are few clues at the site today to indicate the degree of sophistication to which the smelter facility was constructed. The scene in the vintage photo shows that this was not a ramshackle operation assembled piecemeal. The photo really creates an appreciation for the men whose efforts and money were spent to bring this remote area into production.

A Basic History of the Troy smelter.

The history of the smelter does not seem to have been well-documented. The information that I have come across was published in newspaper articles that appeared in the years that the Troy area was active. The accuracy of those articles is unknown.......

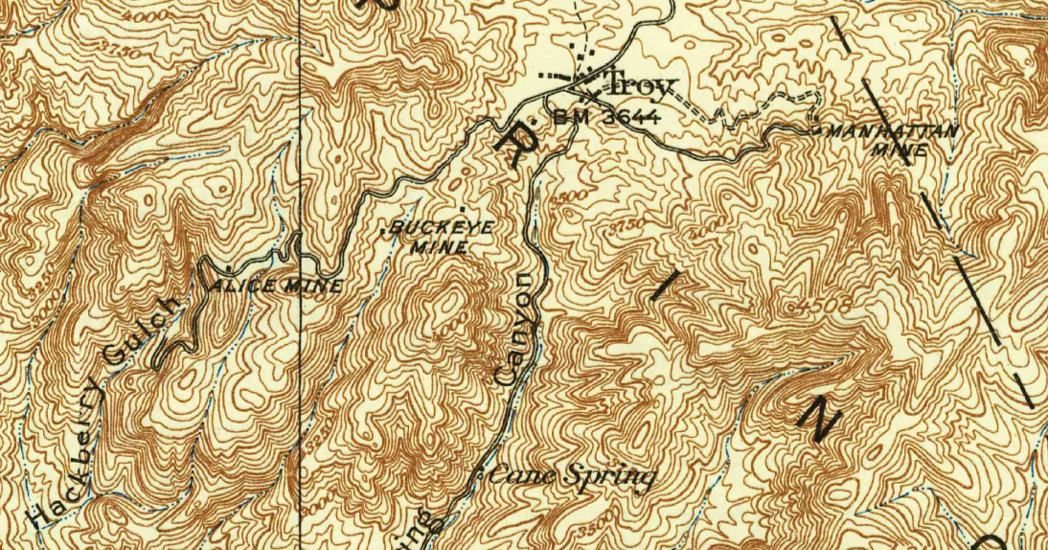

Troy was a mining camp established around 1900 near the crest of the mountains. It was approximately 7 miles northeast of Kelvin, a community on the banks of the Gila River. The Florence to Globe stage/wagon road ran through the camp.

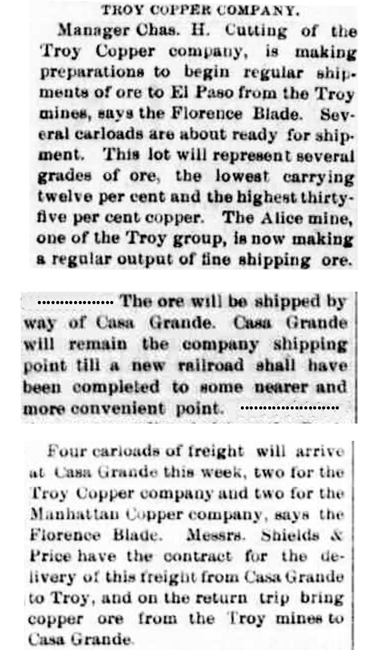

In 1901, two well-funded companies were at work in the Troy area. The New York based Manhattan Copper Company had two sites under development east of Troy while the miners of the Troy Copper Company were busy at four locations west of the camp. Two of the Troy Copper Company's properties were the Buckeye Mine and the Alice Mine. The two companies shared a common manager/superintendent. Mr. C. H. Cutting was in charge of all mining operations at Troy.

The Troy Manhattan Copper Company was created from a merger of the two companies sometime late in 1902 or early 1903. Mr. Cutting remained in charge.

|

The Buckeye Mine was reported to have been the largest of the mines in the Troy area while the Alice Mine may have produced the richest ore.

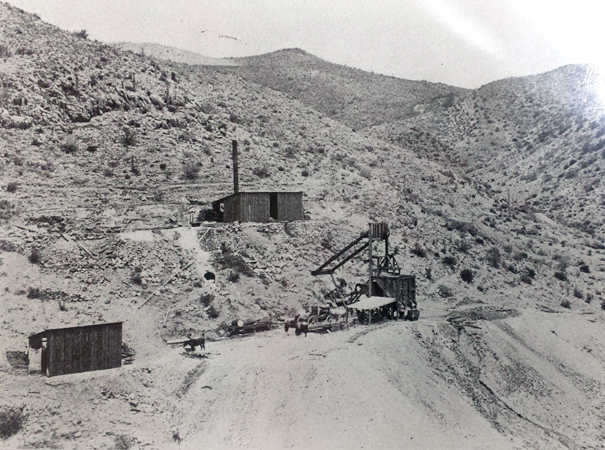

This is an early view of the Alice Mine.

|

The handling of the ores, in 1901, was described in these paragraphs excerpted from an article in the Arizona Silver Belt. This was prior to the construction of the Troy smelter.

|

It was a 75 mile wagon haul from Troy to Casa Grande. There the ore was transferred to rail cars for the ride on to El Paso. It was raw ore that was shipped not concentrates. The materials that were transported were 65% to 88% waste! Production in 1901 from the Troy mines was reported to have been 500 tons of ore shipped with 120,000 pounds of copper recovered. Copper, that year, was selling for about 16 cents per pound. The income generated by the copper weight would have been approximately $19,000. What percentage of that income went to cover transportation costs?

I have not been able to locate any specific information on the types of wagons that were used in the freight and ore transfers between Troy and Casa Grande. The Silver King Mine to the west was known for its use of very large wagons that were often organized into trains.

|

The wagons used in the delivery of supplies to the Christmas mine, 10 miles southeast of Troy, are shown in this photo.

|

At least one freighter who worked the Troy area did have large, heavy duty wagons available. He was able to handle very heavy loads. Was the type of equipment used by Sears the exception or the norm for the freight traffic into and out of Troy?

|

One report noted that it took six days to complete a round trip between Troy and Casa Grande. A contributing factor to the travel time may have been the condition of the road through Kane Spring Canyon. Although, it was only 7 miles in length, there were steep and rocky sections as well as soft sand in the bottom of the canyon to contend with.

This is one section of Kane Spring Canyon as it looks today. There were apparently many times in the history of the canyon road that its condition was pretty similar to this.

|

The February 27, 1902 issue of the Arizona Silver Belt devoted an entire page of articles to the Troy and Manhattan companies, the six mines that were active, and the camp itself. The enthusiastic reporting left little doubt that the Troy area was on its way to becoming one of Arizona's great mining centers. A copy of that page is here.

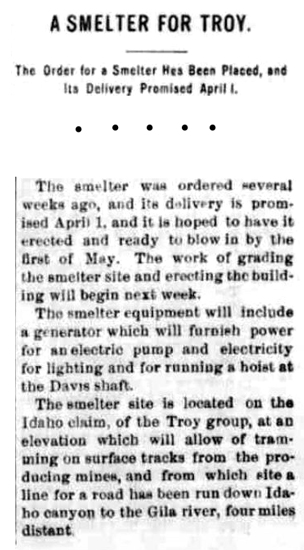

These paragraphs, which announced the purchase of smelter equipment for Troy, were taken from that page.

|

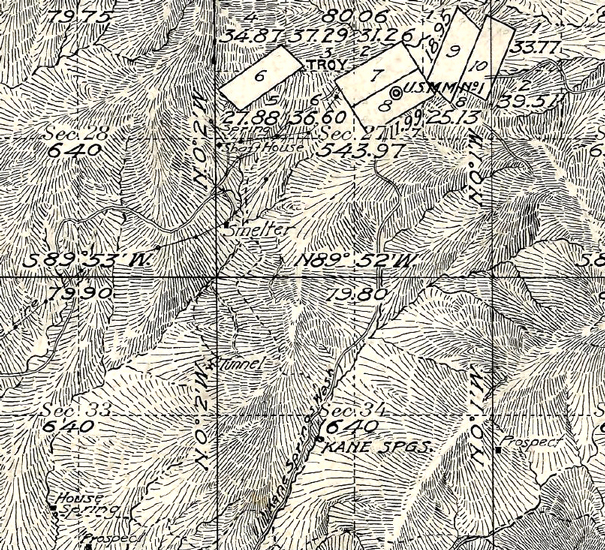

The location of the smelter was shown on this early map. It was southwest of the Troy camp. The smelter was constructed adjacent to the Buckeye Mine. The road down through Idaho Canyon was never built.

|

In anticipation of the upcoming smelter operation, 10 cars of coke were tansported to Troy and stockpiled. The equipment arrived at Casa Grande in April. By the middle of June 1902, the smelter had been assembled and was producing its first copper bullion. The opening of the smelter was announced in a June 12, 1902 article in the Arizona Daily Silverbelt.

|

That same article named the personnel that would make up the smelter crew. Under the direction of the Smelterman, L.W. Morgan, three persons were hired for each of these positions--engineer, tapper, feeder, charge wheeler, and slag wheeler. One person was hired for the crusherman position. The tappers were to serve as shift bosses. Apparently, the intent was to run the smelter for 3 shifts each day. The smelter operation seemed to be well-organized.

The photo of the Troy Smelter is not dated. As it turns out, the smelter was not in operation for very long, so the photo was probably taken sometime between 1902 and 1905.

|

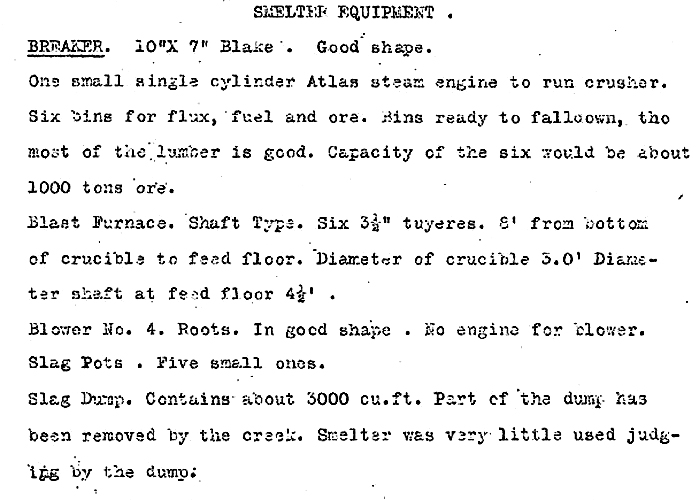

In 1916, perhaps eleven or twelve years after the smelter was shutdown, a list of equpment that remained at the smelter site was included in a report written to evaluate the status of the Troy Mines. That report was created by Mr. A. H. Means for the ASARCO Company. I came across the report at the Arizona Geological Survey website using this link.

|

With the information in the equpment list and the smelter photo, it is possible to speculate how the smelter was operated. The process would have started with the ore wagons pulling up onto the inclined trestle and dumping their loads into the small bins in the center. The Blake crusher would have been used to crush the ore. This fellow, who was standing in front of those bins, may have been the crusherman.

|

From the crusher, the ore materials would have been moved to the large storage bins. According to the 1916 equpment list, those bins had also been used for the storage of flux and fuel. The fuel for this smelter was coke. The fluxes were the limestone and iron oxide provided by the nearby mines.

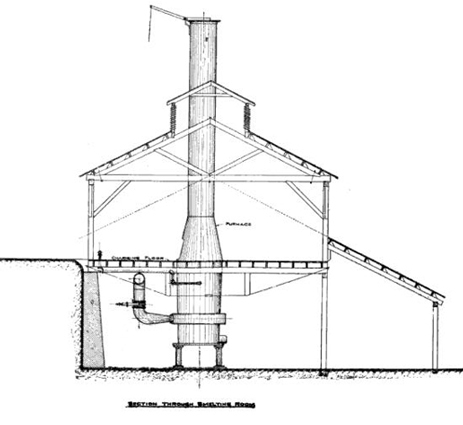

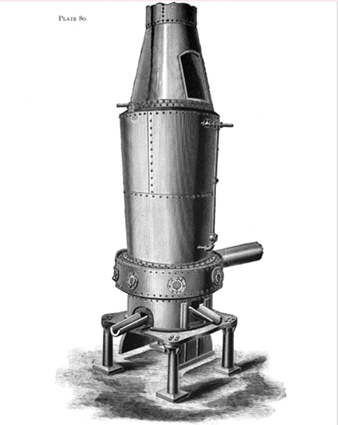

The elevated floor of the smelter that was level with the bottom of the storage bins would have been the feed floor for the furnace. There the charge of ore, flux materials and coke would have been fed into the furnace. These illustrations from an early Allis Chalmers catalog showed a somewhat similar furnace set-up. This style of "shaft" furnace was apparently a "continuous feed" type. Several newspaper reports described the furnace as a 60 ton furnace. Others, however, stated that it had only a 30 ton capacity. The Roots blower in the equipment list would have provided the air necessary for the furnace operation.

|

|

What were the duties of the fellow standing in the shadows next to the furnace ? Was he a feeder? There was not any smoke coming from the furnace stack so it was not in "blast" at the time of the photo.

|

At the appropriate time, the molten materials would have been drawn off through the tuyere drains at the bottom of the furnace. The equpment list noted that the Troy furnace was equipped with six of those. The opening of the furnace would have been the job of the tapper. I am thinking that this fellow might have had that job responsibility.

|

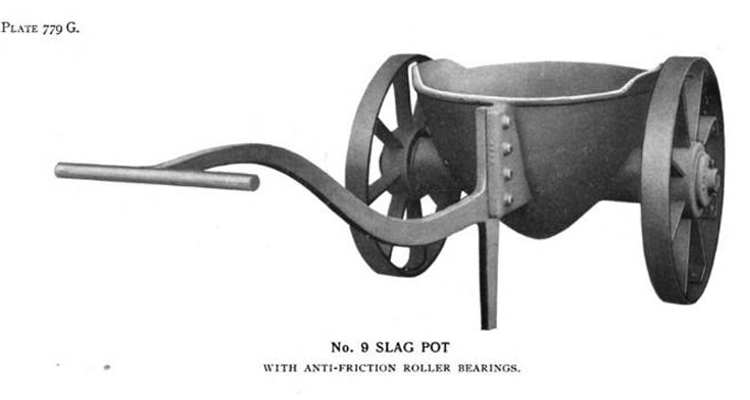

The molten waste materials would have been captured in slag pots and wheeled out to the edge of the slag heap and dumped. The equpment list noted that there were several of these at the site. They may appear in this section of the photo. So were these fellows the slag wheelers?

|

The slag pots may have looked similar to this example from the early Allis Chalmers catalog. According to the catalog, these pots weighed several hundred pounds in themselves.

|

At this smelter, the finished products were bullion bars. A stack of those is visible in the photo. One newspaper article noted a shipment of 67 bars. There are about that many in this group. What were the materials in the wheelbarrows?

|

There is no mention in the equipment list of a bullion mold. This is an illustration of one manufactured by Allis Chalmers. The bars produced in this mold would have looked similar to the bars produced by the Troy smelter.

|

These boilers would have provided the steam to run the engines at the smelter. Is the cart loaded with boiler fuel? In 1905, fuel oil was being used to fire the boilers.

|

With no smoke coming from the boiler or furnace stacks in the photo. I wonder what the occasion was for the photo? It does not appear that it was taken during a production day at the facility. Could this have been a publicity photo for the mining company?

Information that is available on the operation of the smelter beyond its opening date is spotty, and sometimes contradictory. It seems that the smelter was closed down in July of 1902, just one month after the first blast of the furnace. The hoistmen at the Alice Mine had struck to work 8 hour shifts rather than the normal 10 hours. There was reported to have been a car load of copper bullion ready for shipment at the time.

The next report that the smelter was operating was not until January 15, 1903, when the Arizona Daily Silver Belt reported that it had re-opened. In September of 1903, the same newspaper noted that the re-opening of the smelter was imminent so the plant must have shut down again sometime after the January startup.

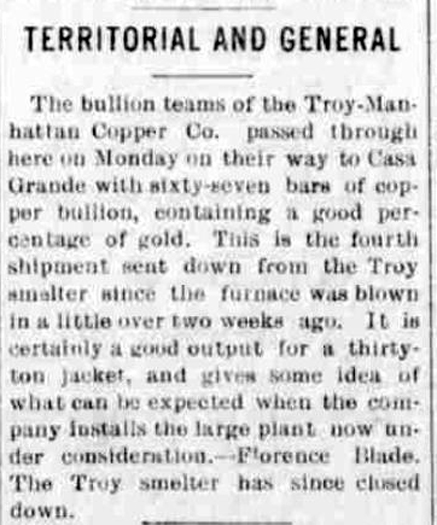

This article published in the Florence Blade in October of 1903 announced that the 4th shipment of bullion since the re-opening in September had passed through Florence. It was also reported that the smelter had closed down once again.

|

There was no indication where the bullion bars went after their transport to Casa Grande.

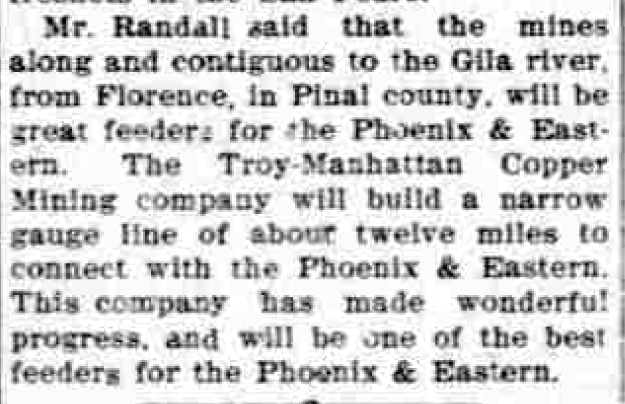

In 1903, this article in the Bisbee Daily Review noted that a narrow gauge railroad line was going to be constructed down from Troy to intercept the Phoenix & Eastern line when it got to Kelvin. There was no indication whether the plan was to ship ore or bullion on that narrow gauge line.

|

David Myrick, in his "Railroads of Arizona Vol II, wrote that the narrow gauge line was never built. Several modern historians have mistakenly included the narrow gauge railroad in their stories of the Troy area. One such reference can be found here.

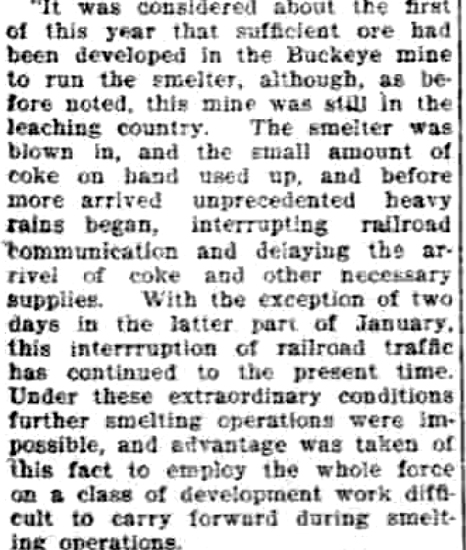

The intermittent operation of the smelter continued. The shutdowns were often attributed to the lack of fuel for the smelter. I have found no references to the operation of the smelter in 1904. In September of 1905, a report to the Troy stockholders described the extended closure that had been in effect since January of 1905. I am not sure that the smelter ever ran again.

|

In 1906, the mining company seemed to have moved away from the smelting of their ore and had agreed to ship 100 tons of ore per day to the smelter at Humboldt. I am not sure that contract was ever fulfilled.

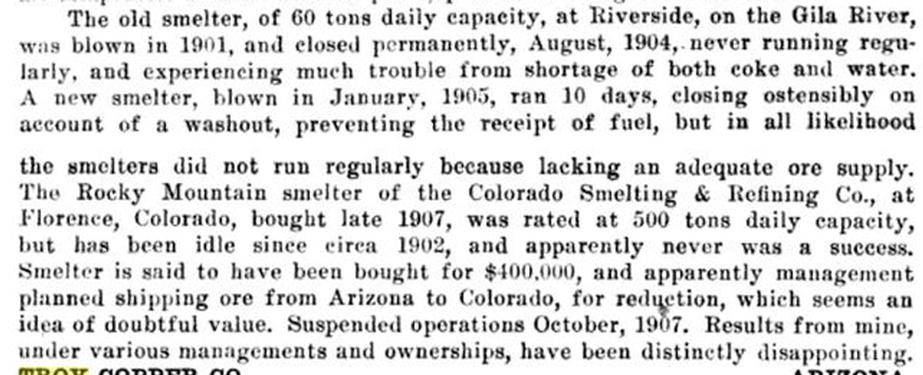

This summary of the mines' history was published in the Mines Register in 1908. There are a couple of errors. The smelter was at Troy, not at Riverside. The first year of the smelter operation was in 1902 not 1901. I am not sure that there ever was a "new" smelter. There was an article in June of 1905 that announced plans for a 100 ton smelter that was to be operational in November of that year. I could not locate any articles that described the construction or operation of that "new" smelter.

The author was probably accurate when he wrote "the smelters did not run regularly because lacking an adequate ore supply".

|

The post office at Troy was closed in 1910. The construction, in 1911-1912, of a smelter at Hayden approximately 15 miles to the east was not enough to stimulate the Troy Mines back into production. There was a trial shipment of ore from the Rattler Mine, one of the Manhattan mines, in 1914 to Hayden. But nothing more. By 1916, the mines at Troy had all but disappeared. This is another section of the Means report that was noted above.

|

So what is the status of the smelter site today? Very little of the infrastructure remains. A pair of saguaros stand in the place of the inclined trestle. Parts of the retaining walls that once held in place the ground at the ends of the trestle are visible.

|

It seems somewhat ironic that there are piles of coke that remain at the site. It was the shortage of this material that was often the blame for the shutdowns of the Troy smelter. Why was this coke not used? These piles have been here for more than 100 years.

|

There are parts of several metal structures that remain. The curved panels of this cylinder were bolted together rather than riveted. This was often done when large structures were assembled at the final destination rather than at the factory. As close as the bolts are to one another, it must have been important that the joint was tightly sealed.

|

Were these relics a part of any of the structures that appear in the vintage photo of the smelter?

|

|

Scattered about the upper level of the smelter site are the remnants of many used fire bricks. The letters embossed into the bricks are "LAPBCo" which may indicate that they were a product of the "Los Angeles Pressed Brick Company".

|

|

Less obvious are the smaller piles of crushed limestone and iron oxide that were used as fluxes in the smelting process. These fluxes came from the nearby mines. This photo is from my trip to the site in 2007.

|

Copper bearing ore fragments that did not make it through the smelter litter the area.

|

In 2007, the shaft at the Buckeye Mine was open. Today, it has a "cover" made from the floor and frame of a mobile home. This structure serves as a support for water pipes that extend down into the shaft. The shaft is probably a water source for the local ranching operation.

|

This was the view down onto the Buckeye Mine dump from Tiger Mountain in 2007. It is huge in comparison to the size of the slag dump. The shaft was reported to be 500' deep with 1000' to 2000' of underground drifting. In 1916, there was a fair amount of equipment still in place at the mine.

|

On my first trip into the area in 2007, I walked over Tiger Mountain to the smelter site and the Buckeye Mine. From there I continued on to the Alice Mine and the Alice Tunnel returning to my truck by the way of Hackberry Canyon. In 2016, I walked the old stage/wagon road up through Kane Spring Canyon. That was the principal route taken by the freighters and miners on their trips to the Troy area.

The Kane Spring Canyon road was an important stagecoach road for many more years than it was the supply road to Troy. One of Arizona's most famous robberies and perhaps the last stage robbery in the state occurred along that section of road. I have summarized that history in a trip report that is here. It is approximately a 10 mile roundtrip walk to the Troy Smelter site by the way of Kane Spring Canyon.

I did not know much about the history of the Alice Mine in 2007. And I did not have access to the photo of its early operation. Using the photos from that trip, here is a bit more information.

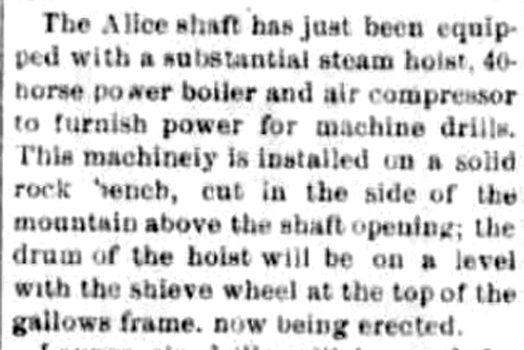

This is a close-up view of the early Alice Mine.

|

Extracted from a 1902 article in the Arizona Silver Belt, this paragraph provided a description of the machinery installed at the Alice Mine. The gallows frame was described "as now being erected". In the photo, the frame is complete and apparently in use.

|

This is a view down onto the Alice Mine Site from the road that connected the mine to the smelter site. The rock bench that was the platform for the mine equipment can be seen to the right. The road beyond the mine dump went to the Alice(Pratt) Tunnel. Pickpost Mountain near Superior is in the distance.

|

These are the equipment foundations that remain on the rock bench.

|

The inclined nature of the Alice Shaft can be seen in the vintage photo. This is what remained at the portal in 2007.

|

Not long after the Alice Mine went into operation, the mine managers decided to approach the ore body from below through a tunnel driven in at a lower elevation. Their reasoning was that instead of hoisting the ore materials up the inclined shaft, it would be easier to chute the ore materials down to the tunnel where they could be trammed to the outside. The tunnel would also be used to drain the water leaking into the mine. By 1904, the tunnel had been excavated to a length of nearly 2300'.

The opening to the tunnel was in a canyon to the southwest of the Alice Mine. The elevation at the opening to the mine tunnel was 500' lower than the opening to the Alice Mine. The Google Earth view below shows the two locations.

In those early days, it was proposed to construct an aerial tramway from the mouth of the tunnel down to Kelvin. That tramway would carry ore in one direction and supplies for the mine in the other. The tramway project was never accomplished.

|

It is interesting that the mining company took great care to build a quality road to the Alice Mine but never made sure that the primary access road through Kane Spring Canyon to Kelvin was of equal quality.

|

It was reported that copper sulfide materials at 2% copper were ignored during the tunneling process. It was considered too low of grade to process. Grades of ore high enough to keep the company in business were not found.

During the WWI years, interest in the area was re-kindled. Unfortunately, the ground at both the Alice mine and tunnel had caved in and access to the ore body was blocked. A crew went to work to re-open the tunnel, but the war ended, and the price of copper dropped so nothing ever became of those efforts.

Four years of work in the 1950's by another crew cleared 1500' of the tunnel. But once again, no production occurred. Several well-known companies did conduct testing in the open tunnel, and the surrounding area but apparently did not find anything interesting enough to pursue.

The Alice Tunnel in 2007 was filled with water and the mine dump was overgrown with mesquite trees.

|

|

I grew up in the general area of the Troy Mines. I had always had the impression that the Troy area had been known as a productive mining location. It was really a surprise to find out that may not have been the case at all. I guess that it did not matter how large and nice the camp was or how much equipment was acquired and set-up, if there was no ore there was no ore.