|

The Scene of Arizona's Last Stagecoach Robbery?

The Kane

Spring Canyon Stage Road,

Some of Its History and its Current Status

|

(This Page was originally created in 2016. In 2023, I returned several times to once again walk the old road. On those trips, we followed the road to the crest of the mountain range near the old mining camp of Troy rather than turning west to the Buckeye Mine. What was learned on those treks has been incorporated here in the orginal report. The new material is presented in blue text.)

Kane Spring Canyon is a major southside drainage of the Dripping Springs Mountains in central Arizona. It heads out near the crest of the mountains and empties into the Gila River west of the town of Kearny.

In 1877, an article in the Arizona Sentinel, a Yuma newspaper, announced that a new wagon road had opened that connected the towns of Florence and Globe City. The construction of this road by a Charles Putnam and his brother, slashed the travel distance between the two towns from 300 miles to 80 miles. A seven mile segment of that Putnam Road was routed through Kane Spring Canyon. The canyon road would remain an important route for nearly 40 years.

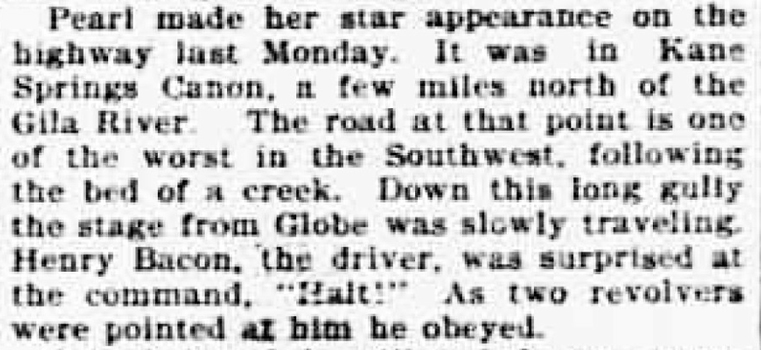

Newspaper articles that have referred to the Kane Spring Canyon Road usually have had one of two themes. The road was damaged or rendered impassable by flooding or there had been a stagecoach robbery. This excerpt from an article that appeared in the Washington Evening Times in 1899 combined those themes in one post.

|

Pearl was Pearl Hart, one of the few women to ever participate in a stage coach robbery. This event attracted so much attention that it is now one of Arizona's most famous and best known outlaw stories. There is more information on this and other similar events farther down the page.

Although I had grown up in Winkelman several miles to the east of Kane Spring Canyon, I had no recollection of ever having been in the canyon. So early in 2016, I headed out that way to see what it was about. My brother in law and I hiked through to the Buckeye Mine west of the old town of Troy. After that trip, I had the chance to look into the history of the road a bit more.

Some History of the road:

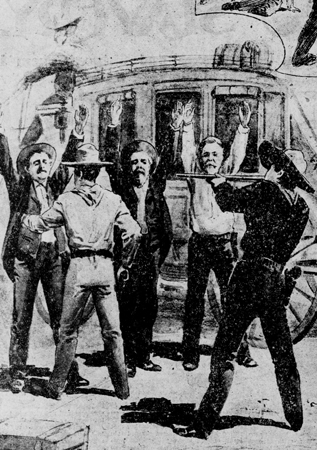

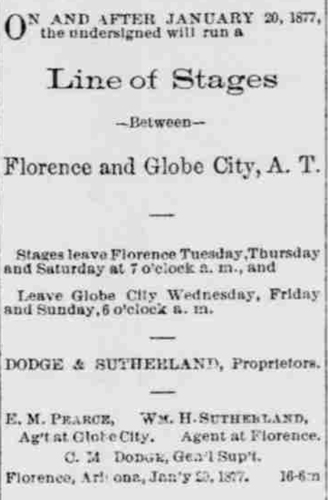

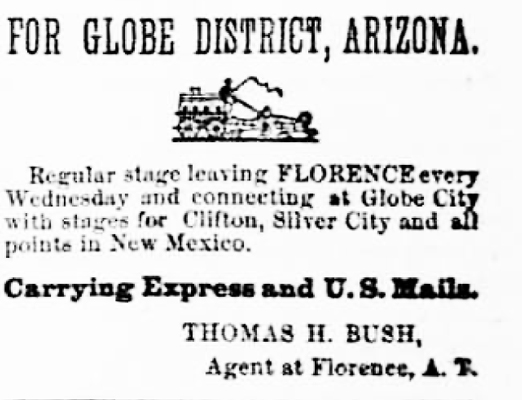

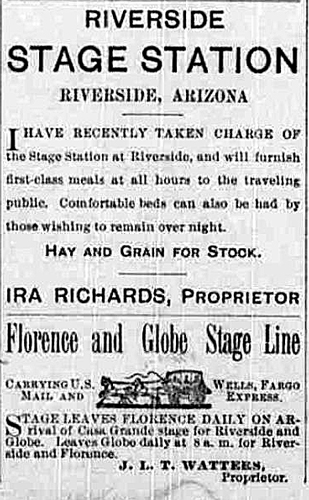

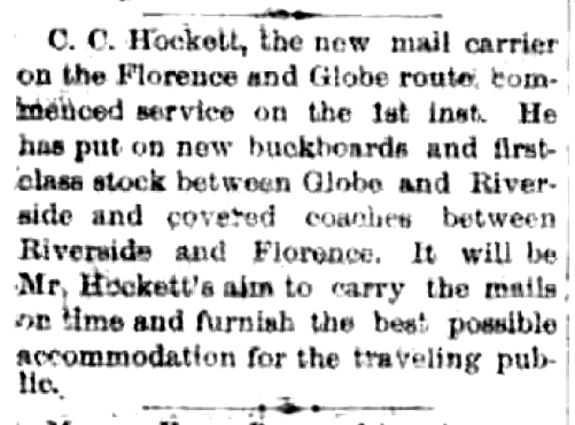

The Florence to Globe road does not seem to have developed into a heavy freight road, but was used more by stagecoach and "fast" freight traffic. Stagecoach operations across the road began in February of 1877. This notice in the Arizona Citizen, a Tucson newspaper, advertised those services.

|

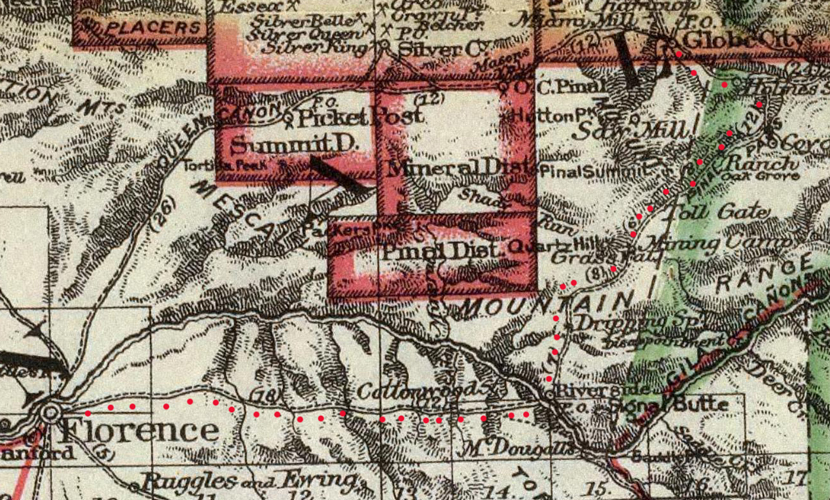

As noted in this 1877 Arizona Sentinel posting, the new wagon road was a link in a more direct route across the Arizona Territory.

|

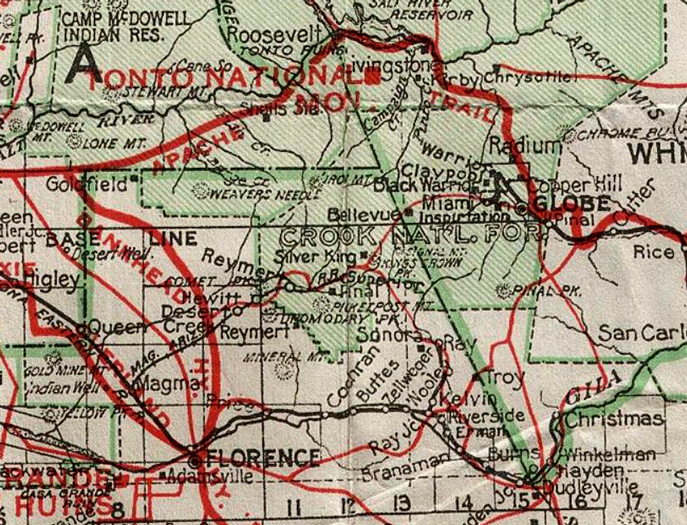

The Florence to Globe City Road is shown on this Arizona Territory Map from 1880. An important waypoint along the route was a station at Riverside on the Gila River. Depending on the direction of travel, Riverside was either at the beginning or end of the trek through Kane Spring Canyon, the Dripping Springs Mountains and the Pinal Mountains. It was 50 miles from Globe City to Riverside and 30 miles from Riverside to Florence.

One traveler in 1878 seemed pretty satisfied that his four horse team was able to make it from Globe City to Riverside in 10 hours. That was an average speed of 5 miles per hour across the mountains. It took another 5 hours for him to complete the trip from Riverside to Florence.

|

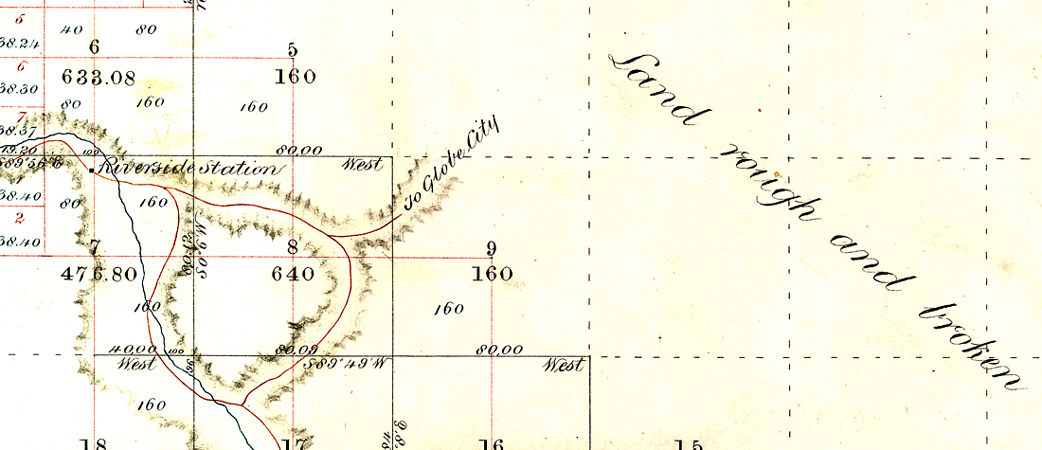

A General Land Office Survey Map of 1880 zoomed in on the area around the Riverside Station. It was located on the westside of the Gila River nearly opposite the mouth of Kane Spring Canyon. In the earliest years, Charles Putnam was the postmaster at Riverside. Federal surveyors would not return to the area and map the "Land rough and broken" until 1908.

|

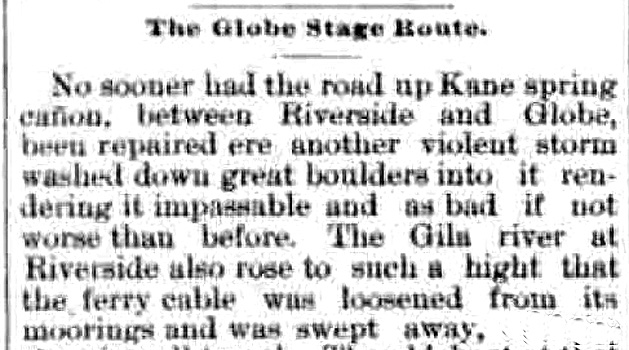

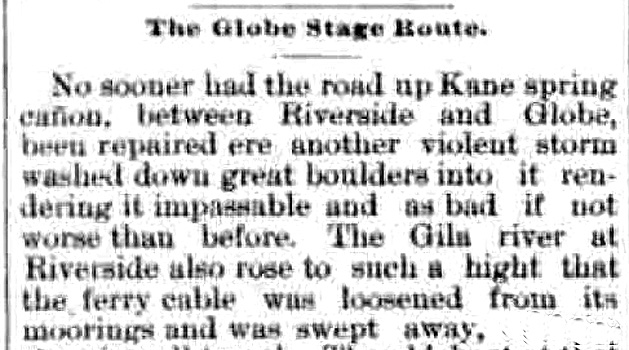

Travel from Florence to Globe City involved a ford crossing of the Gila River at Riverside. Through the 1890's, if the river was flooding, travelers had to either wait it out or turn back. That was not an option for the mail carriers. Several different boats were tried as mail ferries. When those proved difficult to handle in the river currents, a cable was stretched across the river and a mail crate was suspended from it. The crate could hold more than mail. Travelers brave enough could also ride the crate. Apparently, those rides in the mail cart did not always end well. There were several instances in which the occupant ended up in the river.

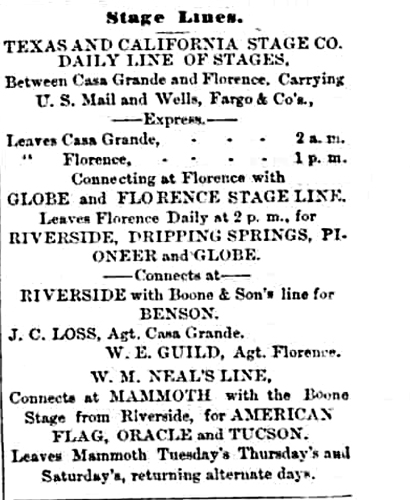

Stagecoach travel schedules published in the 1880's suggest that Riverside was a transportation hub. Arrangements could be made there for travel to Florence, Casa Grande, Globe, Benson, Mammoth, Oracle and Tucson.

|

In 1890, a notice in The Arizona Republican identified the Riverside station as a full-service operation. The scheduling of stages between Florence and Globe had improved from a few times a week to daily service.

|

Mr. Watters would go on to offer non-stop overnight service between Florence and Globe. I do not know how that was accomplished over the mountain portion of the road!

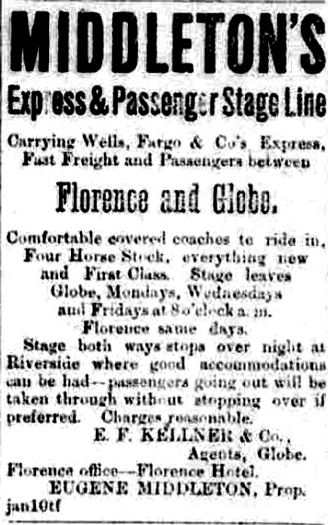

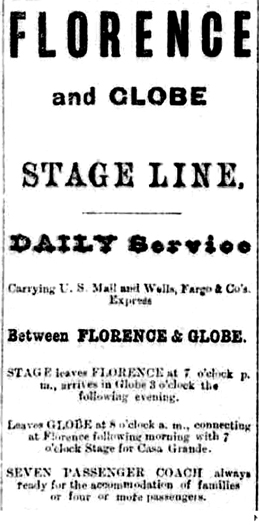

There are not a lot of references to the kinds of stagecoaches that were used between Riverside and Globe. In 1891, two competing stage lines publicized their operations in Globe's Arizona Silver Belt. Each noted the quality of their equipment but did not identify the types of stages that they were running.

|

|

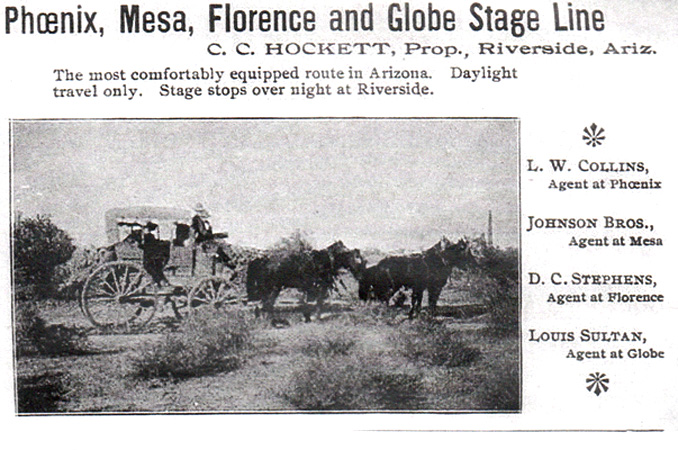

This is a publicity photo that was used in the mid to late 1890's. It appeared in several publications including Out West Magazine. A copy of the photo is at the Pinal County Historical Museum.

|

I have been told that this is an example of a mud wagon. The curator at the Pinal Historical Museum said that this type of vehicle would probably been more suitable for the mountain roads than the larger Concord coaches. Mud wagons were smaller, lighter in weight, and more maneuverable than the Concords. They usually had canvas roofs and sides.

|

Buckboards were frequently used on the road. Several of the stage operators operated in a mixed mode. They used smaller vehicles in the mountains and ran the larger stagecoaches between Riverside and Florence.

|

The condition of the road influenced the kind of vehicles that could be used. There were many times through the years that the road in Kane Spring Canyon was reported to have been damaged or made impassable by heavy rainfall. Notices such as these from 1890 were common.

|

|

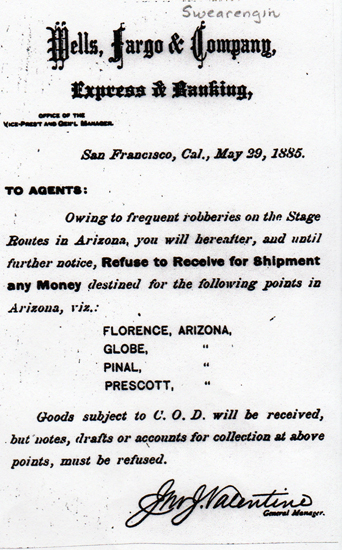

The 1880's and 1890's were a bad time for stagecoach robberies in the Arizona Territory. It was no different along the Florence to Globe Road. In 1885, Wells Fargo issued this proclamation:

|

The Kane Spring Canyon road attracted its share of bad guys. This robbery was reported in the Phoenix Herald on July 16th, 1880.

|

Another stage robbery in 1883 that occurred east of Riverside was more violent. A Wells Fargo messenger was killed and and the stage driver wounded. The robbers were affiliated with the "Red" Jack Almer gang. Several thousand dollars worth of gold and silver were taken in the heist. This news article appeared in the Arizona Sentinel a few days after the incident.

|

Three of the outlaws were soon captured. Two of those three were hanged by impatient vigilantes in Florence. Almer and another fellow were later killed in a shootout near Willcox.

There are many references online to this particular robbery. It is interesting to look those over. A local area newspaper, The Nugget, in 2012 ran a two part series retelling this event. Part one of the series can be found here. And part two can be found here. Apparently the stolen loot was never recovered.

After the robbery, the survivors walked eastward up to Kane Spring where they met the "down" stagecoach on its way to Riverside. After an explanation to the driver of what had happened, everyone decided to spend the night near the spring. The next morning, the group retrieved the body of the dead express guard and continued on to Riverside.

Kane Spring was the scene of another hold up in 1885. The lone robber got a couple sacks of mail, and a few other items from the driver. The robber was not apprehended. This is a transcription of the article published in the Weekly Citizen.

|

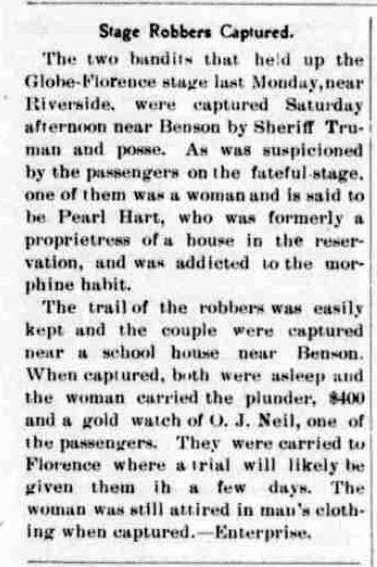

The most well known of all the stagecoach robberies to take place in the area of Kane Spring was one that occurred in May of 1899. One of the robbers was a woman. Her name was Pearl Hart. It was so unusual for a stage robber to be female that the news of this incident caught the attention of the entire nation. There were hundreds of articles written in newspapers and magazines across the country.

I have inserted one brief report of the robbery. This article appeared in The Coconino Sun.

|

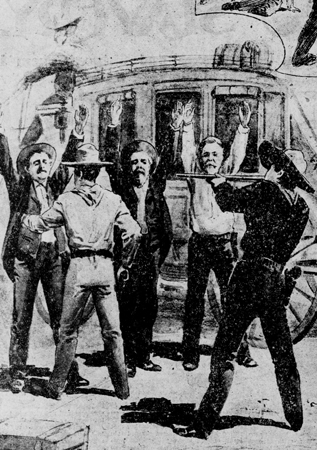

The sketchwork of the stage holdup at the top of this trip report is one artist's interpretation of the Pearl Hart incident. It accompanied a story in the San Francisco Call newspaper. The high level of interest in Pearl Hart's story continued through her two trials, prison sentence and life afterward.

In 2015, the CopperArea.com website published an article retelling the Pearl Hart story. It can be found here. The author of this article made one error in the article. He wrote that the Pearl Hart robbery was the last stagecoach robbery in the United States. That is not correct. There were many that occurred after that date. Today, a holdup that occurred in 1916 in Nevada is accepted as the last known stagecoach robbery in this country.

In "The Encyclopedia of Stagecoach Robbery in Arizona", R. Michael Wilson wrote that the last stagecoach robbery in Arizona was one that occurred near Yuma in 1903. That may not be correct either.

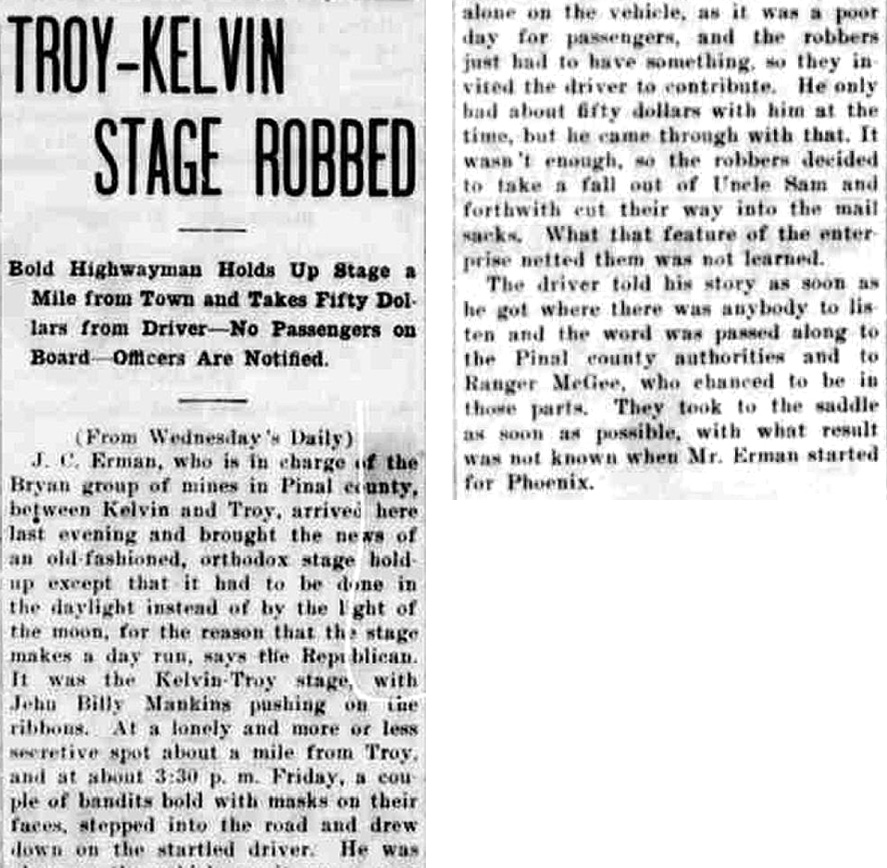

While I was looking for information on the history of the Kane Spring Canyon road, I came across this article that described a stagecoach robbery that had occurred just above Kane Spring in December of 1906. The report was published in the Arizona Silver Belt on December 9, 1906. It was not a very dramatic event, and there was not a lot of loot involved, but this incident should restore the "honor" to Kane Spring Canyon that it really was the site of the last stage holdup in Arizona?

|

Around 1900, the Riverside station was discontinued and a new station was established on the north side of the Gila River at Kelvin. At the same time, a mining camp, named Troy, was booming on the crest of the Dripping Springs Mountains. It was not long afterward that there was a stage station at Troy. This notice appeared weekly in the Arizona Silver Belt in 1902.

|

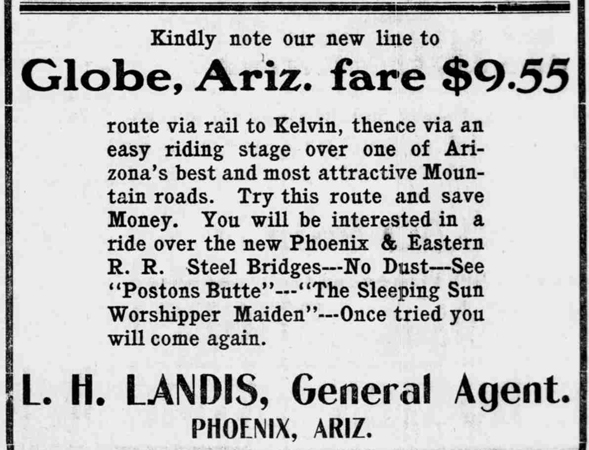

In the summer of 1904, the Phoenix & Eastern Railroad arrived at Kelvin. Stage operators were quick to offer combination rail and stagecoach tickets. The Arizona Republican in 1904 announced this travel opportunity. There may have been some extra enthusiam in the description of the Mountain road.

|

Several newspaper articles in 1905 described improvements in the cable system across the Gila River. Apparently a double cable tramway system had been devised that included at least one "cage" that could carry up to 2000 pounds of freight or four persons and all of their grip.

This is an excerpt from an article that appeared in the Arizona Silver Belt in April of 1905. It summarized a day in the operation of the cables. The cable system became a tourist attraction and a ride on the tramway was often included on train excursions to Kelvin.

|

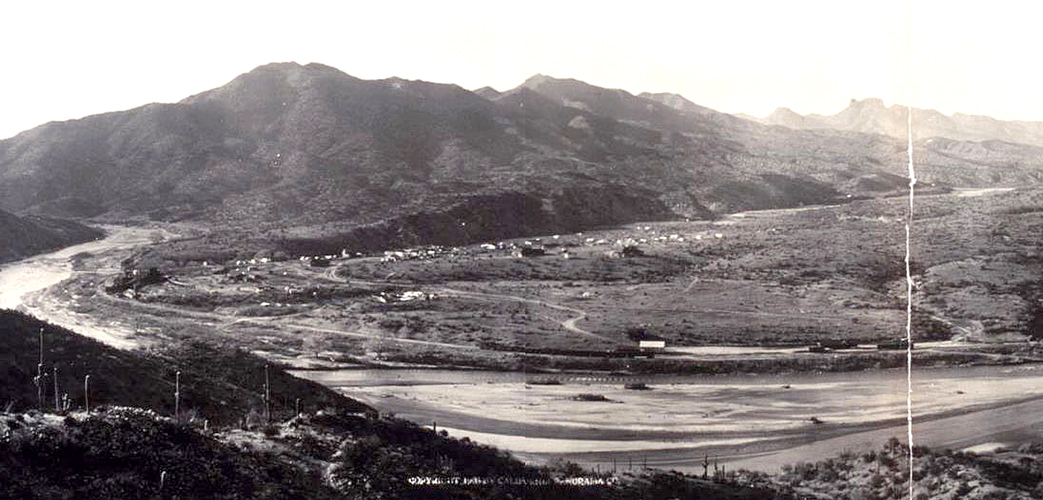

This photo was taken from above Riverside across the Gila River towards Kelvin in 1908. The river channel was quite different in those days. This was before Coolidge Dam. That there is no vegetation in the channel probably indicates the degree to which flooding could occur.

|

This is the 1908 view from above Riverside across the Gila River towards the mouth of Kane Spring Canyon. The road to Troy can be seen leaving the wash to the right just beyond the trestle.

|

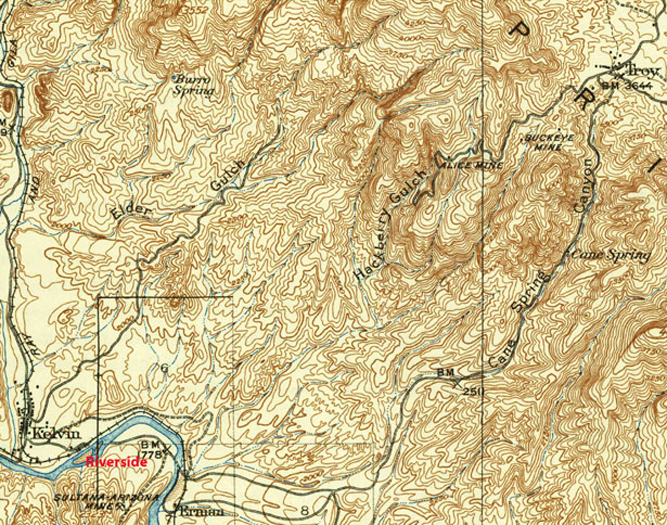

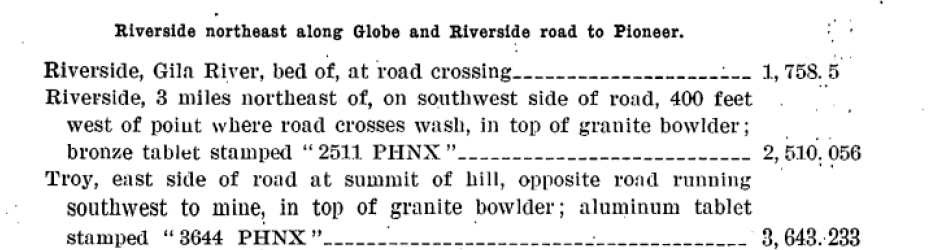

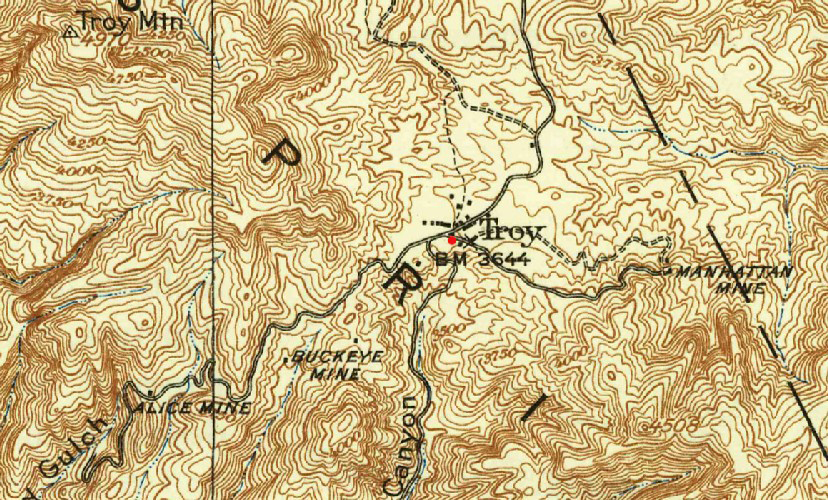

A topographic map that was published in 1910 by the USGS shows the routing of the Kane(Cane?) Spring Canyon portion of the Kelvin to Troy road. There were three benchmarks established to mark the route. Those were BM1778, BM2511 and BM3644.

|

In an index of Arizona benchmarks that was published in 1909, this was the description of the markers. In 2016, I neglected to check on the current status of the benchmarks. In 2023, I thought to do so. Two of the three, BM2511, and BM3644 have survived and are still in place. These benchmarks may have been established as early as 1902.

|

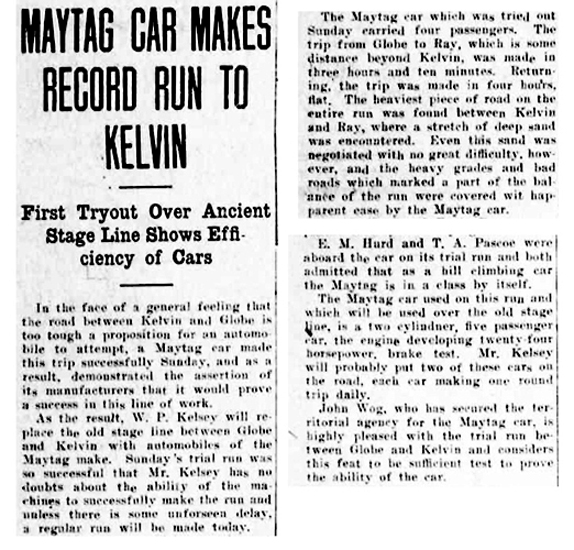

It was around 1910 when the first automobiles began to make their way across the Kelvin to Globe road. One of the stage operators arranged for a demonstration ride to test the feasibility of their use on the mountain road.

The average rate of travel maintained on the test ride was approximately 10mph. That was about twice as fast as the stagecoaches would travel. It is interesting that the most difficult part of the trip was reported as the sand between Kelvin and Ray, not the rocky sections near Kane Spring or elsewhere on the road.

|

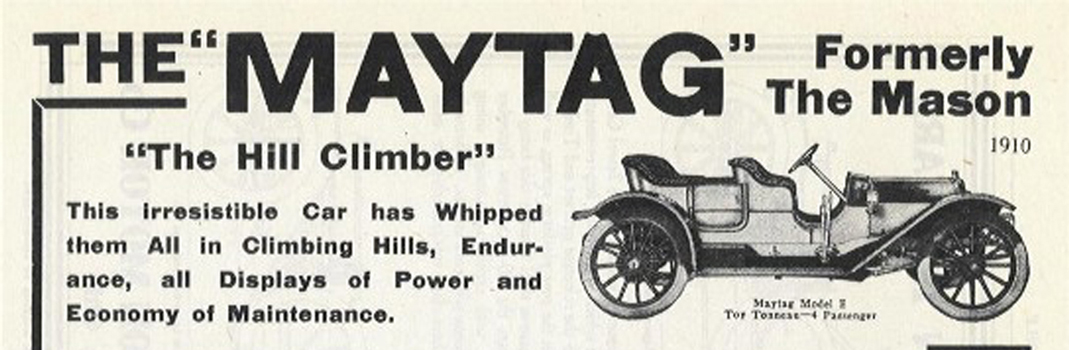

This was an advertisement for the 1910 model year of Maytag automobiles. 1910 was the first year of production of automobiles by the Maytag family. Previously they had manufactured farm equipment and washing machines.

|

In 1912, Governor George Hunt generated controversy when he put a large crew of unsupervised inmates from the state prison in Florence to work repairing and improving the Kelvin to Globe road. This project was a part of his program on prison reform. One of the prisoners' camps was located on the summit above Kelvin.

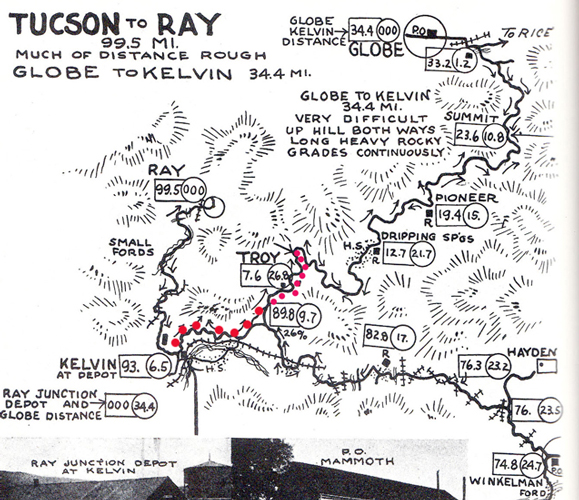

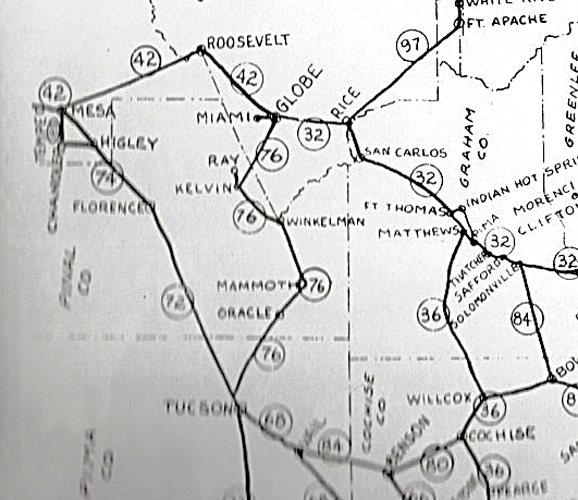

The Arizona Good Roads Association, in 1913, published the first official maps of roads suitable for automobile travel. Included was the route from Kelvin to Globe.

|

This is the index map from the Good Roads Association publication. It shows that for travel from Tucson and other locations in south central Arizona, the road from Kelvin was still the most direct route to Globe and points beyond. Those roads shown in this index were described as Arizona's "Principal Roads".

|

In 1913, an autostage company was running the Velie brand of automobile. The elevation change described in the article was exaggerated by several thousand feet.

|

The Velie 40:

|

The citizens of southern Gila County became so dissatisfied with the poor condition that the road was often in that they threatened to secede and become a part of Pinal County. Those voices caught the attention of the Gila county supervisors and a replacement road to Globe was constructed north from Winkeman in 1916. I do not know how long the Kelvin to Globe road remained open after that. The old road was acknowledged on this 1920 road map. In 1925, it was no longer shown.

|

The Road Today:

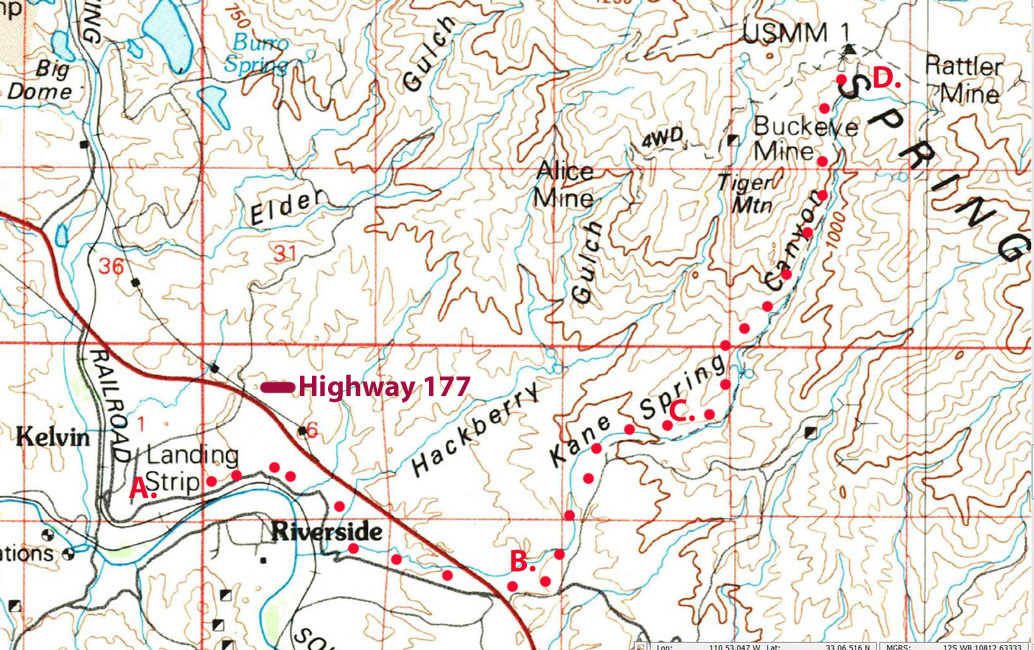

This is a large scale map of the area. It was published in 2003.

|

The sections of road between A, B, and C are the modern incarnations of the Kane Spring Canyon stage road. A comparison to the 1910 topographic map shows a close correlation between the location of those road segments "then and now". Southwest of Highway 177, the road from B to A is paved for a distance. Northeast of 177, the section between B and C will probably require a high clearance vehicle to travel.

The road in the wash east of letter C. is probably better suited for well-equipped short wheel base 4x4 vehicles. In the canyon east of Tiger Mountain and north of Kane Spring, the road has been closed to vehicular travel. Private property that includes the old Troy townsite is posted against entry.

This is the current view of the mouth of Kane Spring Canyon at the Gila River. The channel is clogged with vegetation as compared to the view from 1908 above. The wooden trestle from the early days of the railroad has been replaced with steel culverts. The buildings across the river are in the community of Riverside. It was subdivided in the 1960's. At that time, the old stage station was still standing.

|

In Section 8 of the 1880 GLO map, the road to Globe City is shown in Kane Spring Canyon. On the 1910 map, that section of road is on the ridge to the south of the canyon. This is the 2016 view into that portion of the canyon. There are few signs of any modern travel in the wash. The Dripping Springs Mountains are in the distance.

|

Geology played a role in the routing of the stage road. It would have been impossible to have run the road in the section of the canyon that parallels the old road between B and C on the modern map.

|

This is the view toward the mountains as seen from the road between B and C. The tall mountain to the far left is Tiger Mountain.

|

At letter C. on the modern map, the road drops into the wash. I have no doubt that this scene today is probably very similar to one that the early stage and freight team drivers would have experienced. The only difference that I can imagine between the "then and now" views would be the kind of tracks in the wash. It is hard to believe that this was once one of Arizona's principal roads and that it was that way for nearly 40 years.

|

A few hundred yards up the wash, there is a another chokepoint in the canyon. The road did not go this way. Back downstream there is a bypass to the south around this narrow point in the canyon. Today, it is easy to miss that turnout.

|

It is places like this along the old road that I was glad that we chose to walk the route instead of trying to drive it. This is along the bypass of the chokepoint in the photo above. The first time that I was here, there were two jeeps returning from up in the canyon. One had broken a front axle maneuvering around in the wash. The broken vehicle had to be strapped up this particular spot. It seems that it was not only the early travelers who had issues with this road.

|

This Google Earth view of the upper Kane Spring Canyon shows how it is a natural corridor to the crest of the mountains. The dark mountains in the far distance are the Pinal Mountains south of Globe. The old road can be seen in the lower left portion of the photo just above the words "Google Earth". It crosses the wash to the north side of the canyon for a ways and then drops into the bed of the canyon as the drainage turns to the north. The road remains close to the bottom of the canyon until just below the crest of the mountains.

|

The benchmark identified as BM 2511 on the early 1910 topo map is located in the lower left corner of the photo above near the words "Google Earth". As noted in the description, the marker was located "400 feet west of point where the road crosses the wash". In the photo below, the red dot indicates the location of the benchmark. As it was described in 1909, it is "on southwest side of road......in top of granite bowlder".

|

In this close up view of the benchmark, the stamp "2511" and "PHNX" is as described in the early index. On modern maps, the benchmark is identified as BM2510. The disc was identified as being made of bronze.

|

These photos are of the section of road where it has crossed to the north side of the wash in the GE view above. The road was usually much closer to the channel than it was here. There was some excavation required to create this piece of the road bed.

|

|

These were some of the obstacles that were bypassed by the section of the road that was constructed away from the wash.

|

Just upstream from the well-preserved section of road, the route is once again in the wash bottom. Would the stagecoaches have been able to travel the road in conditons similar to this?

|

In 2023, there were two fences across the wash that were not there in 2016. There were gates in each. The signs asked that the gates be kept closed.

|

It is a little more than 1 1/2 miles up to Kane Spring from BM2511 on the 1910 topographic map. It is not a difficult walk. Driving the route would be a bit more challenging. It is sometimes necessary to deviate away from the old road bed. The road is sometimes grown over or the cutbanks at the edge of the wash are too tall and steep to mess with.

Kane Spring is accurately placed on the 1910 map, but not the 2003 version. The spring has formed behind a massive rock formation that spans the width of the canyon.

|

Mother Nature has been at work cutting through the natural rock dam. She still has a bit more to do.

|

The waterfall at Kane Spring has been bypassed on both sides. The 1910 topo map indicates that the roadway was to the west of the channel at this location. That would be to the left in the photo. I have not been able to find any references to any road construction or repair work done at this location.

The bypass on the right may still be driveable. It would take extreme care and a properly outfitted vehicle to accomplish. How interesting it would be to be able to go back in time and watch the early stage, freight and automobile drivers negotiate this stretch of road!

|

This is what remains of the old roadbed that bypasses the waterfall to the west. It looks really narrow. I wonder if passengers rode or walked this section of road?

|

The road surface on the westside bypass was solid rock. What was the traction like for the early iron wheeled vehicles?

|

Today, there is a small grove of trees growing in the channel at the top of the waterfall.

|

This is looking south down Kane Spring Canyon from the top of the bypass. I think that if I had been a passenger on a stagecoach, this would have been a section for me to walk.

|

In this view to the south, the old road bed is seen angling down to the wash below the cliffs to the right.

|

North of the waterfall, an old retaining wall marks the exit from the westside bypass back into the wash.

|

It is a very restful place at Kane Spring. Was this also a rest/camp area back in the early days of the Kane Spring Canyon Road? One early report stated that the routing of the road had been chosen because it had been a path that was used by the early native peoples.

|

North of the Kane Spring waterfall, there are a couple of tilted rocky ledges in the channel. There does not appear to have been a way around these.

I am thinking that even in the best of conditions that the drivers of the stages, wagons and automobiles would have had to pay very close attention to their task at hand to negotiate these obstacles.

How could this terrain have not been an advantage for the bad guys?

|

A bit further north, there is another shady place. This pretty much had to be the location of the old roadway.

|

And there was one more ledge to negotiate. The rocky outcrops to either side would not have permitted any route other than over the ledge.

|

There is interesting geology in the bottom of the canyon. Here there are ripple marks that could have been formed by wind blowing across ancient sand dunes. Those sand dunes were later transformed into the rocky layer that makes up this formation.

= |

This is the view down the canyon from a hillside north of Kane Spring. The Gila River drainage runs from left to right in front of the mountains in the distance.

|

On north from Kane Spring there are sections of the road that are well preserved and sections that are not so much. The roadbed is generally very narrow.

|

|

In 2016, this sign on a gate in a fence that crossed the road announced that vehicular access was no longer permitted on up the canyon. In 2023, that sign had been replaced with one that simply asked that the gate be kept closed.

|

At the top of a cliff on the eastside of Kane Spring Canyon there is an interesting pipe or rod. What does it mark?

|

Approximately, 1 mile north of Kane Spring, the road leaves the canyon and climbs up a granite like ridge toward the crest of the mountains. The alignment of this section of road does not match that of the 1910 topographic map. A Google Earth view of this location shows an abandoned section of the road to the west. This is the one section of the road that does not really conform to the road's position as it was depicted on the 1910 map.

|

This view down Kane Spring Canyon from up on the ridge would not have been much different than the one experienced by the passengers on one of the early stagecoaches, buckboards or automobiles. Tiger Mountain is the tall peak to the right.

|

This is the windmill that is shown on the large scale map at letter D. It is very close to the boundary of the private property that is a part of the Troy Ranch. In 2016, this is where we left the Kane Spring Canyon Road and traveled west to the Buckeye Mine. In 2023, we continued north on the Kane Spring Canyon Road.

|

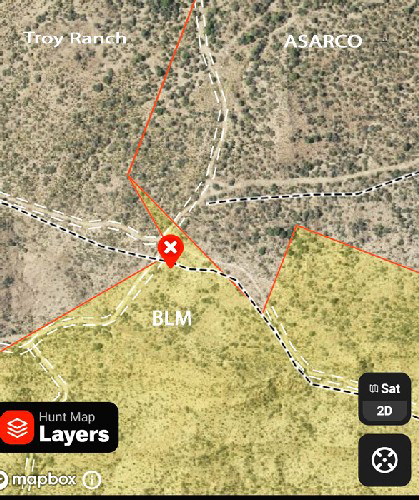

The ownership status of the lands in the Upper Kane Spring Canyon is shown on this section of a BLM map. The orange colorization represents public BLM land. The white is private property. The irregular shape of the private property in the northern part of the map is derived from the arrangement of several of the mining claims that were once active around the mining camp of Troy. The windmill in the photo above is shown on this BLM map.

|

In 2016, we knew that there was private property in the area of the old townsite of Troy. We had chosen not to travel in that direction because we were not certain where the boundaries were between public land and private property. In 2023, we had the use of a navigation program that provided greater detail on the status of the properties along the old road. This screenshot, from the ONX app, identified the private property owners and showed their boundaries. The waypoint marks the location of BM3644. It appeared that the Kane Spring Canyon Road which approached the benchmark from the south was on public BLM lands. It would not be trespassing to travel to the benchmark.

|

Using the location of the benchmark as a reference, it can be seen on the early 1910 map that the Troy camp was largely located to the north and west of the marker. Today, that area is on the property of the Troy Ranch.

|

There is a sign along the westside of the road that indicates that the Troy Ranch is private property and there is to be no trespassing in that direction.

|

This is the current status of BM3644 as it sits "in top of granite bowlder" at the crest of the road. This marker has also been renamed on modern maps. It is now identified as "BM3643".

|

The disc is not in very good condition. The "3644 PHNX" stamping is quite weathered. I have not ever seen a benchmark in such poor shape. Is its current condition due to vandalism? Had someone tried pulling the disc ? It is interesting that the description of the marker indicates that it is aluminum and not bronze.

|

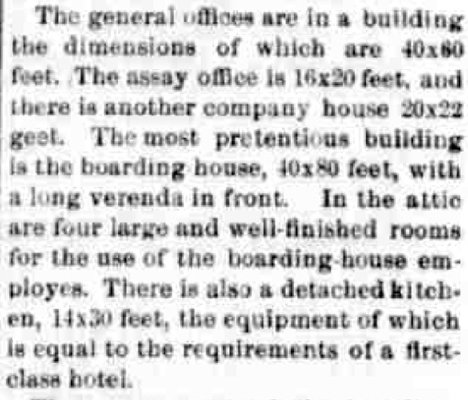

In "Ghosttowns of Arizona", it was noted that the post office at Troy was established in 1901 and discontinued in 1910. Saloons were prohibited so the camp was considered to be a "Model Camp". Permanent buildings included a general store, hospital, boarding house, union hall, assay office and other offices associated with the mining company. The miners lived in tents. Newspaper articles reported that there was a community baseball team and a band. The musical instruments had been provided by the mining company. Horse races were popular events held during holiday celebrations.

This is an excerpt from one article published in the Arizona Silver Belt that described some of the buildings in the town. From this description, it may be possible to identify the large building in the early photo of the camp that was dated around 1901.

|

|

In 2023, This was the view of the town site taken in the same direction as the early photo. The red marker in the photo is at the location of BM3644 and the blue marker indicates the location of the large building in the early photo. The remnants of a building could be seen there.

|

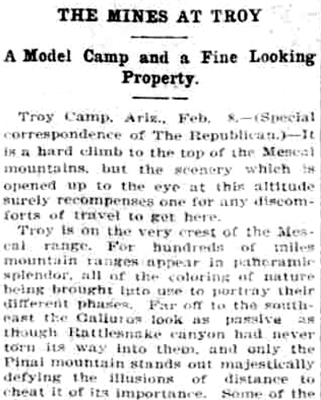

Also noted in some of theearly newspaper articles were the scenic views that could be had out from Troy. This was a section of an article published in the Arizona Republican in 1902.

|

This is the view out to the Mescal Mountains to the northeast. The road cut for highway 77, the modern road to Globe, can be seen just above the pass between the two hills in the foreground. Even though it is not possible to travel over to the actual Troy townsite, the views from the crest near the benchmark justify the effort made to get here.

|

The Pinal Mountains, in the distance, are in this view to the north.

|

Even though the area near the benchmark was at the edge of the Troy Camp, it is evident that this area had at one time been occupied. These stone alignments could have marked the location of a miner's tent site.

|

Old cans that had been sealed with solder, and many pieces of sun-colored glass were scattered about.

|

While saloons were not allowed in Troy, it was not illegal to have alcohol. Many broken liquor bottles were seen as we walked around. This was the base of a beer bottle manufactured in the early 1900s by William Franzen and Son in Milwaukee Wisconsin.

|

There is an interesting assortment of ceramic type materials in this photo. The white pieces are modern, while the tan pieces looked to be pieces of pottery.

|

Scattered about were chunks of the copper ore that had been produced in the mines nearby.

|

For four wheel drive/high clearance vehicles, it is an easy drive north of Highway 177 approximately 1 mile to where the road drops into Kane Spring Canyon. From there, the walk along the old road to the crest of the mountains is approximately 3 1/2 miles. The scenery and the history associated with this old road makes this a very worthy destination for a great backcountry adventure!

|