|

The

Riverside Tragedy--the last official sighting of the Apache Kid

|

On November 2nd 1889, a group of eight Apache convicts, who were being transported from Globe to the state prison at Yuma were able to overcome their guards and escape from custody. This headline from the November 9th Arizona Silver Belt announced the incident. Sheriff Reynolds was Glenn Reynolds, the sheriff of Gila County. William "Hunky Dory" Holmes, was the deputy on duty, and Eugene Middleton was the stagecoach driver. Not mentioned here was that one of the prisoners was the Apache Kid, a former Apache scout. The escape occurred on a section of road that connected Riverside, a stage station on the Gila River, to the town of Florence.

Having grown up in the general area where the escape had occurred, I was interested in its actual location. There is a lot of material available on the story of the Apache Kid, but few authors have reported on the location of the escape with any kind of useful detail. There was one exception. This description is from an article, "The Escape of the Apache Kid", published in 1931. Mertice Bruce Knox, the author, wrote:

| "The road over which the clumsy, heavily loaded Concord coach traveled in the faint light was a very bad one, up and down steep grades and through sandy washes. The Ripsey Wash, about a quarter of a mile in width, opens into the Gila about four miles from Riverside. The old road crossed this, then climbed the hill through a narrow, crooked ravine some halfmile long, striking at the top what is now the state highway to Florence. The horses were winded and sweaty after struggling through the deep sand of Ripsey Wash, and when the hill was reached Middleton suggested that the officers and some of the prisoners walk up the hill to relieve the horses and get warmed up." |

Unfortunately, Mrs. Knox did not provide any diagrams or maps to accompany her report.

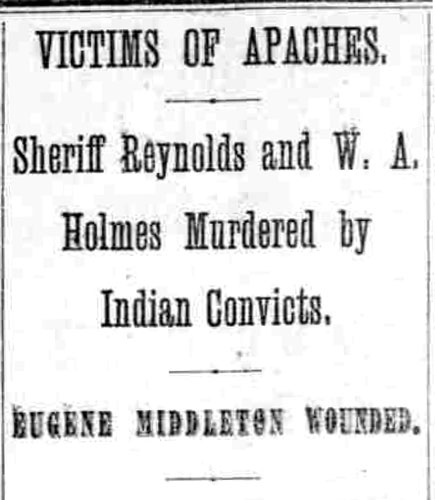

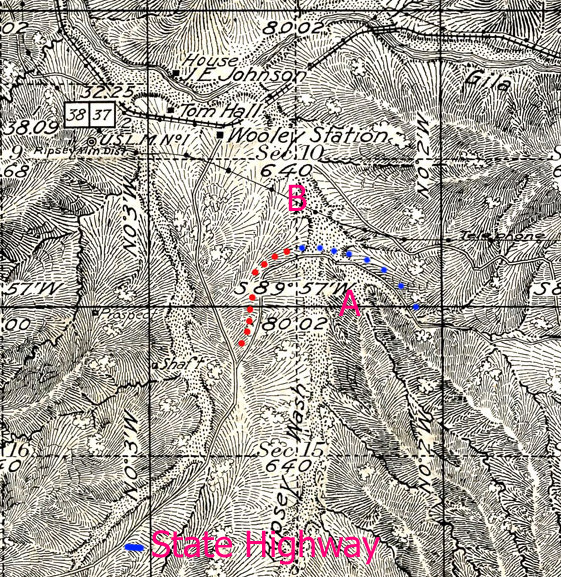

This map section is from an 1880s map of Pinal County. While it shows the stagecoach road that connected Riverside to Florence, there was not enough other information included to help locate the scene of the Apache Kid's escape.

|

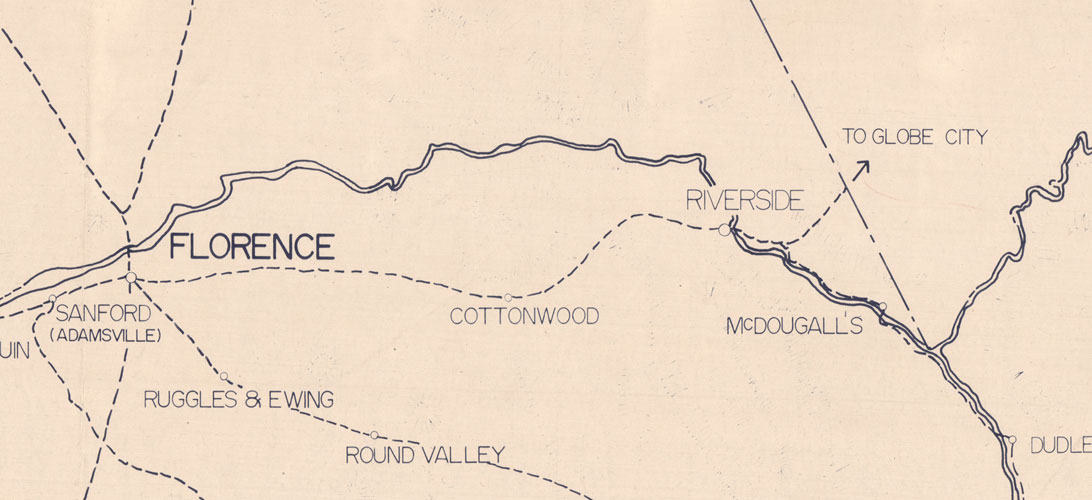

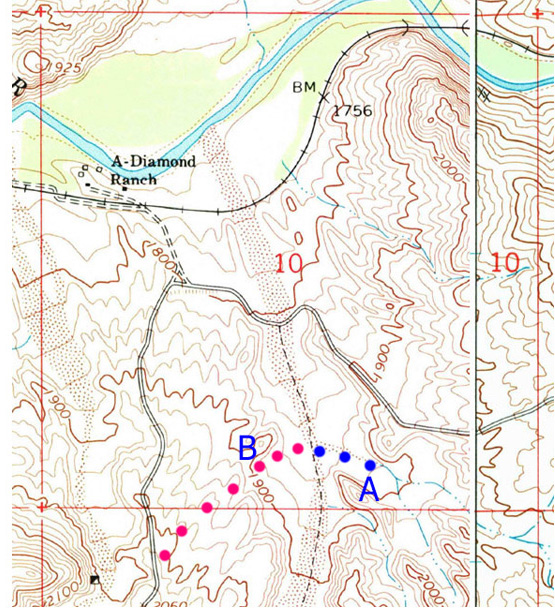

These topo maps from the early 1900s included the roads, outlines of the terrain, and indications of elevation. The red dots highlight the section of the road that seemed to be the best fit for the description provided by Mrs. Knox. By the times of these maps, the Riverside station had been abandoned and a new community named Kelvin had been established.

|

In this section of the 1924 GLO Township map of the area, the road segment from the topo maps above could be identified. Mrs. Knox had noted that the old road connected to the State Highway at the top. That State Highway was labeled on the Township Map. Landmark features A and B , together with the grid lines outlining the perimeter of Section 10 made it possible to transfer the location of the old road segment to a more modern map.

|

Once the old stage road had been sketched onto this modern map, its location relative to current landmarks could be seen. What is most obvious is that the old stage road is south of the current road that connects Kelvin to Florence. It has been written that the paths of the current road and the old stage road were the same. That may be true elsewhere, but not at this location.

|

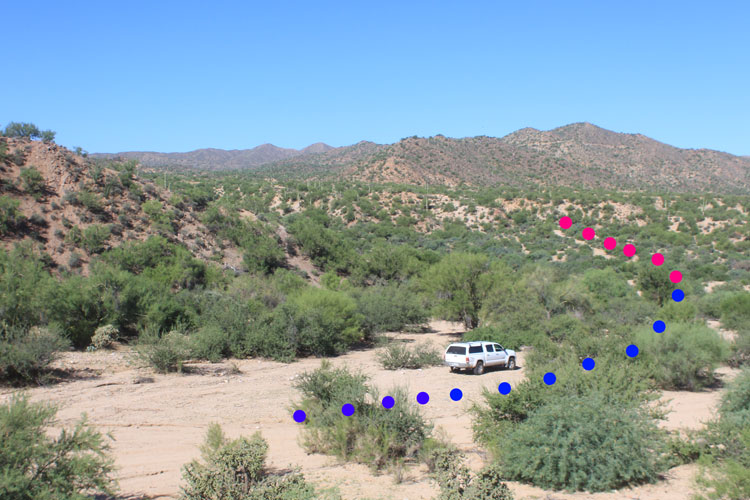

With an idea where the old road was located, it was then possible to use Google Earth to "flyover" the area south of the current Kelvin/Florence Highway. The trace of an old road could be clearly seen. This was enough info for me to drive out to the area and look things over.

It did not take long to find a narrow, crooked ravine and a steep hill like that described in the Knox article. Landmarks seemed to match up pretty well, but I was not 100% certain. Of course, there were no signs that announced that this was the scene of the Apache Kid's escape. Neither were there pieces of stagecoach sticking up out of the sand to confirm that this was the correct location.....

Was there someone familiar with the area who might be able to provide information? I posted a Google Earth Image of the road on a Facebook page for local folks and asked for assistance. After a few days, it was suggested that I make contact with a Doug Hamilton who lives in Kearny. That contact was made. It turned out that Doug is an expert on the escape story. He has given many presentations on the subject to historical organizations and other groups. He was very gracious in his response to my request and confirmed that I had located the correct section of road. He then shared some of the information that he had learned about the location. A return trip to the old road was in order.

Photos from the old road and the site of the attack:

It appears that what actually happened during the escape is unknown and still debated upon today. There have been many versions of the incident presented. Some are quite different from the others. I have tried to be brief in my comments . There is a lot more information out there.

The sand wash in the foreground of this photo is the side canyon that was the stagecoach " road" on the east side of Ripsey Wash. The point of land on the left is the landmark that I had identified as "A" on the maps above. The stagecoach would have traveled down this side canyon, crossed Ripsey Wash, and then turned to the southwest to begin the climb away from the wash.

|

This is a closer view of what may have been the route out of Ripsey Wash to the west.

|

On my first walk in the area, I disturbed this fellow. He did not appreciate my presence at all! I was much more cautious afterward!

|

Soon after leaving Ripsey Wash, the best choice for the route was through this narrow ravine. This matched pretty closely with the route description provided by Mrs. Knox.

|

In about 100 yards, the ravine opened up and what was definitely a constructed road left the small wash and climbed out to the southwest,

|

As confirmed by Doug Hamilton, this was the hill referred to in the Knox article. If the passengers were not out of the stagecoach beforehand, they were let out at this point. This was the steepest part of the road. Mrs. Knox wrote that it was generally agreed upon that the Apache Kid and one of the other Apaches were considered to be too dangerous to be trusted outside of the coach, so they were shackled and kept inside. The other six Apaches were handcuffed together in pairs, and were directed to walk between the Sheriff, who followed behind the stagecoach, and Holmes who brought up the rear.

|

It was on the hillside that the Sheriff and the deputy were attacked by the Apaches. The struggle began when the stagecoach pulled ahead and went out of sight. In this distant view, the red line indicates the location where the body of Sheriff Reynolds was found afterwards. Mrs. Knox wrote that Mr. Holmes' body was found approximately 50 feet below that of Reynolds. Although there are several theories, it is unknown for sure, how the Apaches were able to get the drop on the two men. That the sheriff had allowed the Apaches to walk behind him was a serious mistake.

Mr. Holmes may have died of a heart attack during the struggle. He was not shot. The Sheriff was wounded by rounds from Holmes' rifle and his own weapons. The Apaches were particularly brutal in their assault of Reynolds. The attack on him, apparently, continued even after his death.

Middleton, the driver, was initally unaware of the battle going on behind him. His thoughts, upon hearing the gunfire, were that the guards were target shooting as they walked along the road.

|

In her report, Mrs.Knox included a photo that she had taken at the bottom of the hill. Her intent was to show that there had been a rock cairn erected as a memorial to Sheriff Reynolds and Deputy Holmes. Floods had washed away the monument, but Mrs. Knox drew an arrow onto the photo to show where it had been located.

|

The current vegetation has altered the view that Mrs. Knox had. This was as close to her position that new photos could be taken. A saguaro now appears on the skyline.

|

This low mound of rocks marks the location where the Sheriffs' body was found after the attack. The monument had been noted in a newspaper article back in 1893. Doug Hamilton and his friends came across this mound on one of their explorations.

|

The stagecoach ended up approximately 75-100 yards on up the grade from where Reynolds had fallen. In addition to the 8 Apache convicts, there had been a Mexican prisoner by the name of Jesus Avott. Avott had been on the ground with the guards and the Apaches. When the battle began, he ran to the stagecoach to warn the driver. As with the other aspects of this story, there are several versions as to what happened around the coach. The bottom line is that the driver was wounded and fell to the ground. The two Apaches escaped from the coach and the Mexican prisoner fled into the brush.

It seems that for this incident, that the Apache Kid was pretty much a bystander. His active participation came near the end of the struggle after he was released from his shackles.

|

This is the view from the upper part of the old stage road. It is not as steep as the lower portion. The view is to the northeast back towards Ripsey Wash. The road to the right is the modern Florence/Kelvin Highway.

One version of the escape story has the stagecoach destroyed off to the side of the road when the horses panicked after the shooting began and the driver had fallen off the coach. Another version has the vehicle calmly parked on the road where it was noticed by a passing cowboy. In that version of the story, the stagecoach was eventually recovered and put back into service for several more years.

After the escape of the Apaches, Middleton, although seriously wounded was able to stagger back to the stage station at Riverside. After a lengthy recovery period, he remained in the stage business for a while before moving on to other endeavors.

Avott, the Mexican prisoner, who did not participate in the attack, may have been assisted by the passing cowboy. He eventually made it to Florence where the news of the attack was sounded. Avott was later granted a full pardon for his original crime.

The governor of the Arizona territory set-up a reward for a "dead or alive" capture of the Apache Kid. It was never claimed. The escape was the last official sighting ever made of the Apache Kid. His whereabouts, afterwards, and his ultimate outcome were never confirmed. Pretty much every unexplained and violent encounter with the Apaches that occurred after his escape was blamed on him.

For a version of the escape story that is quite different, check out the Wikipedia entry called "The Kelvin Massacre". I am not sure how the word "Kelvin" has come to be associated with the escape story. The town of Kelvin was not established and named until 1899, ten years after the escape of the Apache Kid. For many authors, the steep hill where the attack occurred has come to be called "The Kelvin Grade".

In a follow-up article on the escape, the Arizona Silver Belt newspaper in Globe used the phrase "Riverside Tragedy" to describe the event.

"The Escape of the Apache Kid" article by Mertice Bruce Knox can be downloaded as a PDF file here.

The November 9 1889 Arizona Siver Belt article on the escape of the Apache Kid can be found here.

The November 23 1889 Arizona Silver Belt article on the Riverside Tragedy can be found here.